LAUGHING WHILE 2013 - 2019

LAUGHING WHILE

2013 - 2019

Discussions of identity feature prominently in contemporary culture, championed most recently by the transgender community. However, writers such as Hélène Cixous have been interrogating the basis of gender and the claims made on its behalf for decades. In groundbreaking pieces such as 'Sorties' and ‘The Laugh of the Medusa’, Cixous dissects the assymetrical relationship between sex and power in which male values are always (often invisibly) privileged and she outlines a vision for a kind of radical artistic practice that could oppose the old, toxic system. This is écriture féminine.

It is a form of experimental writing that could be made by women or men which challenges the dominant order in which knowledge and reason are seen as pre-eminent values unproblematically transmitted through the medium of language but in reality, are persistently marshalled to sustain patriarchal power. No one style is compulsory for écriture féminine but qualities of radical playfulness, ambiguity and multiplicity are prized (James Joyce was identified as an innovator of feminine writing avant la lettre). Cixous is not an easy read always and it would be naïve to pretend that her ideas had much traction in popular culture but they have inspired generations of students, philosophers and artists.

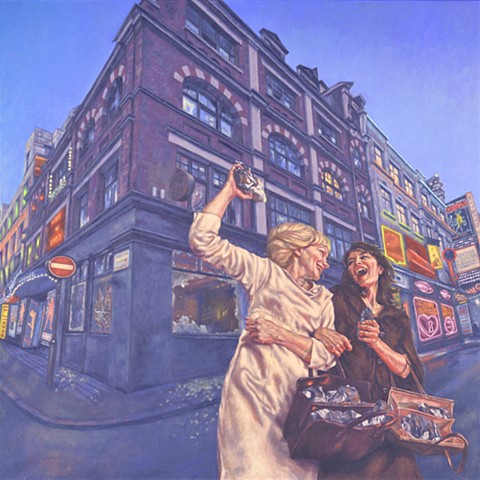

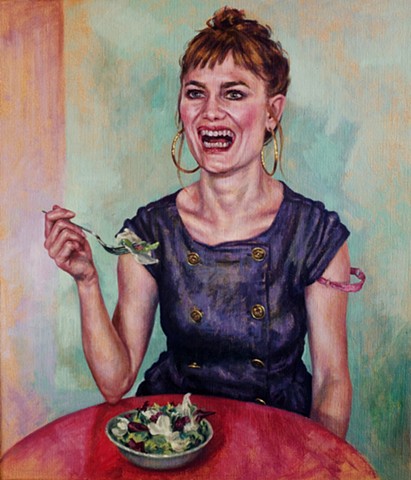

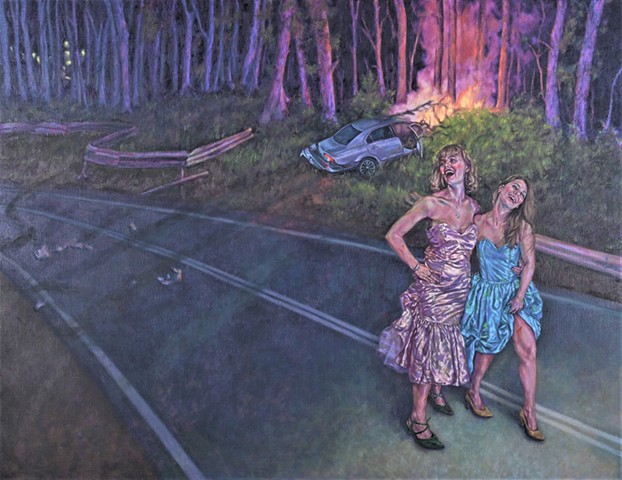

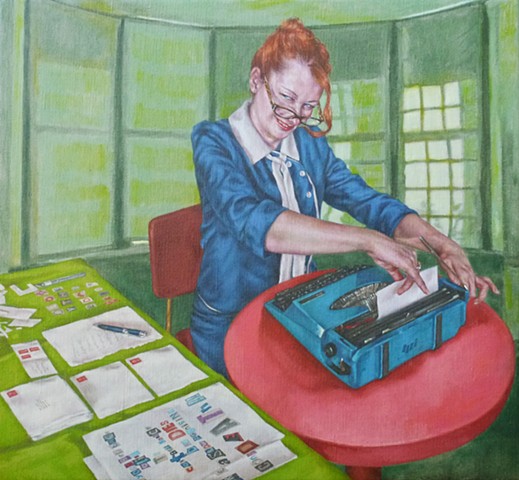

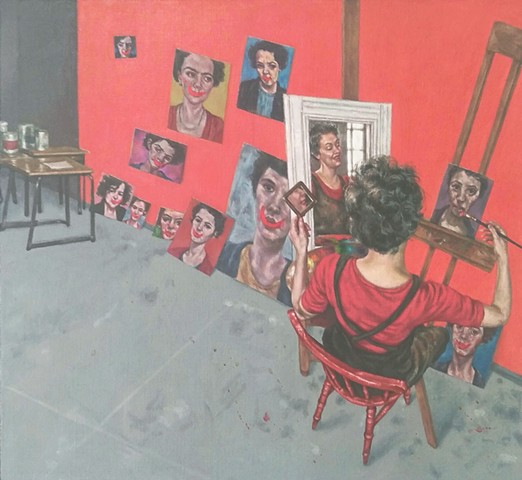

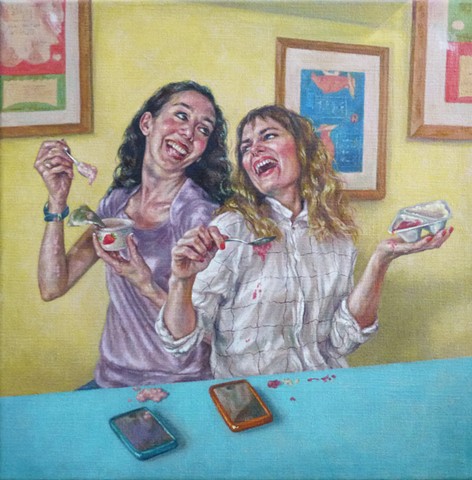

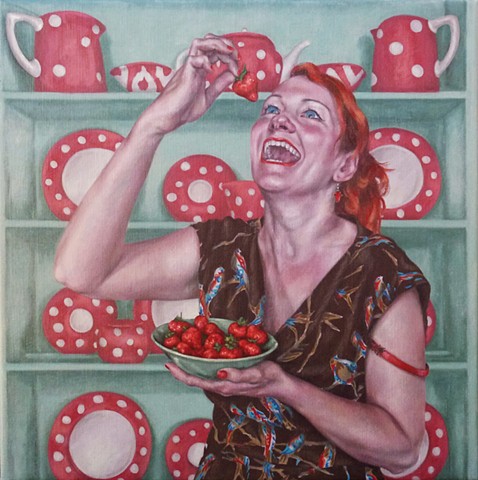

For me, écriture féminine is most alluring as an enduring provocation. When I paint images depicting female pleasure, excessiveness or impropriety I think of Cixous, her ideas and her stories. She shows us how resistance can take so many forms - the cultural prohibitions on women being so numerous. In one essay (‘Castration or Decapitation?’’) Cixous tells the story of the Chinese general Sun Tse who decapitates a group of women he is trying to train as soldiers, so disconcerted, so disgusted is he by their persistent laughter and refusal to take his orders seriously. This resonates with me deeply. Acts of political resistance come in many forms and when I paint images of women laughing, eating, reclining, reading or simply looking, I am always cognisant of the fact that the most seemingly innocuous actions can be subversive.

I am committed to a tradition of oil painting that does not align formally with écriture féminine in terms of its espousal of formal experiment. Indeed, the proponents of ‘feminine writing’ would have to join a long queue of thinkers and practitioners in the art world who would line up to assert that my chosen medium is obsolete. However, I cannot see why an oil painting is automatically any more anachronistic than a novel if it responds thoughtfully to contemporary life.

I reserve the right to take what I find useful from any philosophy. I am in profound sympathy with the aims of écriture féminine and I love the provocative clear-sightedness of a writer like Cixous: her work is a spur to me as I pursue my own vision.