TINGLE - TANGLE

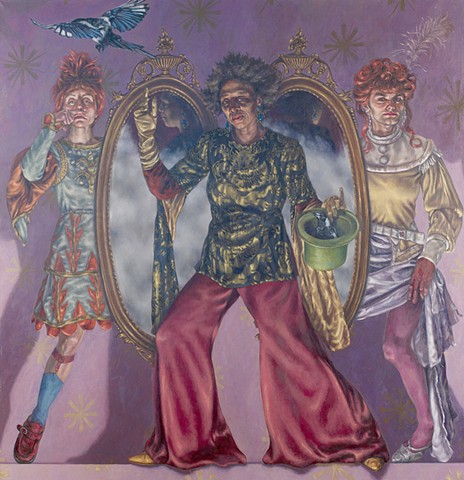

Halls’s large painting Cecilia the Astonishing & her lovely assistants Masculinum/Femininum, 2009 (oil on linen, 157 x 152 cm) is part of her ‘Roxana Halls’ Tingle-Tangle’ series of eleven works originally exhibited at the Royal National Theatre, South Bank, London. The German Tingel Tangel arose from the vaudeville scene in the 1890s. These intimate theatre variety shows, a kind of cabaret, were often ‘little more than a raised stage at the side of a cheap restaurant or pub, where aspiring (or down-and-out) entertainers would perform.’i Whilst some were reputable, more were peopled with male clients and soubrettes who sang risqué songs onstage, and then circulated among their audience selling erotic postcards, encouraging the consumption of alcohol, and advertising their services as sex workers. Whatever the term’s origins – the clink of money on a platter passed around after acts is one suggestion - there’s no doubt it was used disparagingly. Yet Tingel Tangel was popular in the 1920s and ’30s (there are at least three German films of that era with that title) until many shows and sites were closed down by the Nazis who considered their satirical humour a threat. Several of the characters in Halls’s series actually existed, albeit in other contexts such as British music hall. Halls found a reference to Masculinum/Femininum as Weimar performers, but no visual image of them so here she invents her own. In Cecilia the Astonishing & her lovely assistants Masculinum/Femininum the latter appear to be one person split in two, their genders blurred. Their orange hair piled high and ornate gowns are juxtaposed with men’s garters and sensible shoes. This mirroring hints at the multiplicity of roles assigned to women in the burgeoning era of commerce, Americanisation, and the New Woman that characterised the Weimar republic. The protagonist herself, magnificent in silk pantaloons and brandishing a conjuror’s top hat, points upwards where a bird takes flight on the shallow stage; it’s not the traditional dove, though, so beloved of ordinary magicians, it’s a magpie, that most opportunist of birds. A risk-taker; a thief of all things shiny. If Halls sees herself as a bit of a magpie, selective in her eclectic sources, foraging for costumes, then there is another bit of self-referentiality here: Cecilia is framed in a pair of ornate, smoke-filled mirrors that open like a giant clam, allowing us a simultaneous view of her head in profile and from behind in the manner of Renaissance portraiture. It’s a reminder that isn’t painting all just smoke and mirrors? As Melanie Duignan writes, ‘In these economically embattled times, the Tingle Tangle pictures defiantly suggest how, through the alchemy of paint, an inventive aesthetic can transform the mundane - cardboard sets and charity shop costumes - into extraordinary spectacle. They also demonstrate the enduring capacity of painting to fascinate and beguile.’

Marie-Anne Mancio - Catalogue Essay - No Reserve

Exhibited in

DIE AUGEN DER ROXANA HALLS, Haus Kunst Mitte, Berlin 2023

NO RESERVE, Leicester Contemporary, Leicester 2021

TINGLE-TANGLE, Royal National Theatre, South Bank, London 2009